Study validates split-second exam of retinal health

(The article was published in the UW Medicine Newsroom.)

UW Ophthalmology researchers have validated an approach to measuring how rod photoreceptors, the cells in our eyes responsible for night vision, respond to light in living eyes. The approach might one day enable earlier detection of serious eye diseases like age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

In studying the normal, healthy retinas of humans and rats, the investigators reported seeing consistent cellular-level responses to a prescribed amount of light: The outer segments of the rod photoreceptors shrank immediately and rapidly, then slowly elongated.

"This is the first time we've been able to see this happen in rod cells in a living eye," explained Ram Sabesan, associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He was co-corresponding author of the study, published today in the journal Light: Science & Applications.

The findings, he said, reinforce the feasibility of a fledgling technology called optoretinography. In just a few years, it has emerged as a tool that might predictably display molecular hints of retinal disease earlier than any conventional diagnostic instrument.

“Rod dysfunction is one of the earliest signs of many retinal diseases, including AMD and retinitis pigmentosa,” Sabesan said. “Being able to directly monitor the rods’ response to light gives us a powerful tool for early detection and tracking treatment responses.”

In 2020, he and colleagues published findings about optoretinography’s ability to show similar shrinkage in cone receptors, the specialized cells responsible for color and daytime vision.

Seeing similar action with the smaller rod structures was “like watching the eye’s molecular machinery spring into action in real time, without electrodes, dyes or surgery,” said Tong Ling, assistant professor at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, and the study’s co-corresponding author. He was also a coauthor of the 2020 findings.

In this study, Ling’s team measured rod cells’ response in rats while Sabesan tested the eyes of three people. Both exams showed minute contractions of rods’ outer segments that occurred within 10 milliseconds of light exposure — a span shorter than a single flap of a hummingbird’s wings.

Optoretinography integrates multiple technologies:

- One is adaptive optics, used by astronomers to compensate for atmospheric turbulence and generate sharp pictures of stars and other celestial objects. Incorporating adaptive optics into a conventional retinal camera enables the differentiation of rods from cones in a human eye.

- Another is interferometry, which splits a beam of light into two paths and recombines them to create patterns of light and dark by which scientists can precisely measure minute distances and surface irregularities.

As a result, Ling said, ophthalmologists can distinguish and measure cellular structures with “far higher spatial resolution [than conventional diagnostics] while making the detection process completely contactless.”

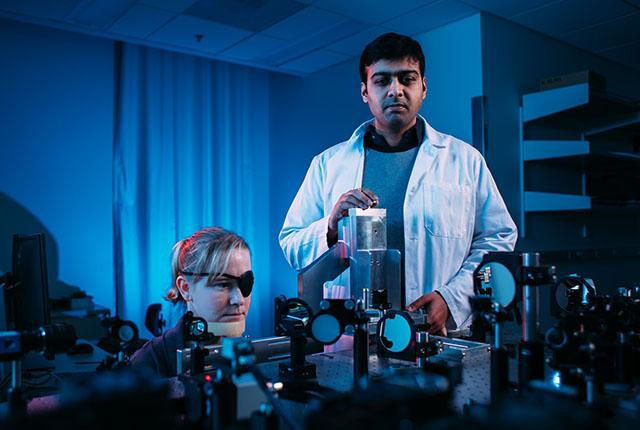

Sabesan acknowledged that this testing is “in early days and not a readily available diagnostic for clinical use.” He described the optoretinography test setup as “decidedly homemade,” with components covering most of a 4-by-8-foot table.

Its promise, though, is to outperform current diagnostics of retinal function, which he said lack sensitivity, take significant time and can be onerous for patients.

The next step, Sabesan suggested, would be to study rod photoreceptor function in larger patient cohorts, including people with elevated disease risk and those already diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration, to ascertain early manifestations of the condition.

Beyond mapping rod dysfunction, the findings also hint at personalized, noninvasive vision monitoring and accelerated clinical trials aimed at stemming retinal diseases.

The project brought together biomedical engineers, physicists and clinical scientists from the Singapore Eye Research Institute, Nanyang Technological University and the University of Washington.

Funders of the research included the U.S. National Institutes of Health (U01EY032055, EY029710), Research to Prevent Blindness, the George and Martina Kren Professorship in Vision Research, Dawn’s Light Foundation, and the Kren Engineering-based Medicine Initiative.